In defense of fangirling on the internet

It’s almost hard to believe we’re back here again, defending fangirls, but we are.

“Fangirling”, that effusive gushing of glee, excitement, and praise that is often attributed to teenage girls in fandom, is becoming a household word. It’s a catch-all term, imprecise, but generally accepted to refer to any happy, enthusiastic feels focused on a single person, place, or thing.

So if fangirling is such a positive sentiment, why would anyone hate it?

“Call me cynical, but there’s something rather uncomfortable about this trend where grown women act like over-excited One Direction fans - over the smallest things,” wrote Radhika Sanghani in The Telegraph “At best, it’s just a bit cringey, and at worst, it’s an insincere squeal that says far more about the woman writing it than the one it’s dedicated to.”

I know Sanghani, a dedicated feminist who I’ve agreed with on many other issues, isn’t intending to paint a misogynist argument here, but it’s impossible to escape the gender politics of fangirling, especially when every one of her examples of famous fangirlers (Lena Dunham, Jennifer Lawrence, Taylor Swift, Anna Kendrick) are women. It’s right there in the word fangirl. This is something reserved for women, this hysterical, shrieking exercise in overemoting.

It’s also something young people do, especially young people on the internet. It’s another example of our language evolving, as emojis, slang, intentional typos, and alphanumeric linguistic inventions are introduced and adopted as commonplace speech. Sanghani takes issue with the clapping hands emoji and the #fangirl hashtag, but emojis and hashtags are just examples of our written language adapting to the digital landscape. As we communicate through increasingly visual mediums, often with character limits, an emoji, hashtag, or Harry Styles gif is frequently the simplest, clearest expression.

But another thing about fangirling is that the stereotype of the loud, hysterical over-the-top squeeing is not actually an accurate representation. It’s there, but fangirling language takes many forms. The all-caps incessant shout of adoration is only one.

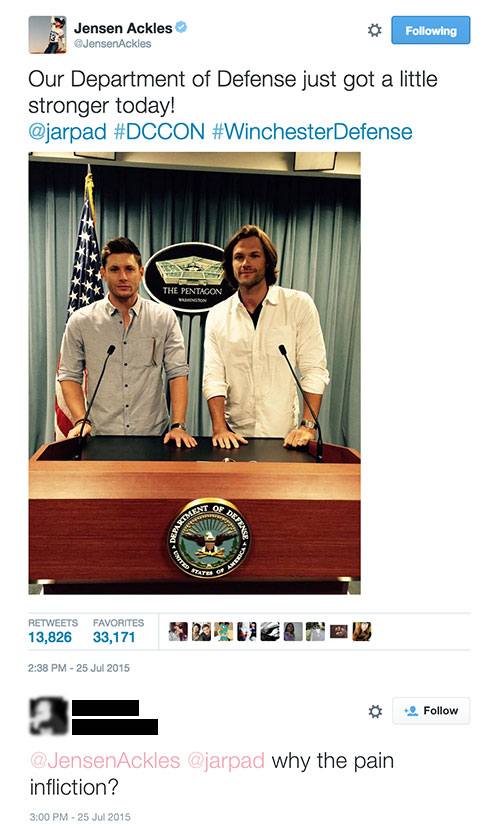

There’s also, for example, the ironic anti-fangirling fangirling that involves lovingly calling your favorite celebrity an asshole, complaining that his selfies are causing physical pain, and calling yourself and fellow fans trash, usually all lowercase without punctuation. Not Sanghani’s "OMG seriously wanna be her right now.” as much as “oh noooo”, "send help", or the beloved “i can’T EV EN”.

Fangirling can take as many as forms as fangirls themselves do. It’s a varied and constantly-changing culture that cannot be dismissed with one fell thinkpiece.

But to get back to Sanghani, it’s true that most of these styles of fangirling are unlikely to land you a followback or reply from whoever you’re fangirling over. So why do it? Sanghani says these types of tweets “rarely [lead] to solid, meaningful relationships.” This is where she’s flat wrong. Sure, maybe telling Zayn Malik on Twitter that his new haircut is causing you extreme levels of personal distress isn’t the best way to become friends with Zayn Malik, but it’s sure a great way to meet and commiserate with other pained Zayn fans. Friendships are forged through fandom every day on the internet — lasting, compelling, worthwhile friendships, it’s not despite fangirling. It’s because of it.

L M F A O show of hands, how many of you have made actual incredible friends through fangirling?? pic.twitter.com/xS2wtaxknz

— Sam (@SamMaggs) August 2, 2015

And if anyone ever wants to connect with me because they liked something I made or wrote or put into the world, please absolutely by all means tweet me your appreciation of the thing. Or, tweet me the deep anguish that last Sherlock promo picture caused you. I’m right there with you, girl.